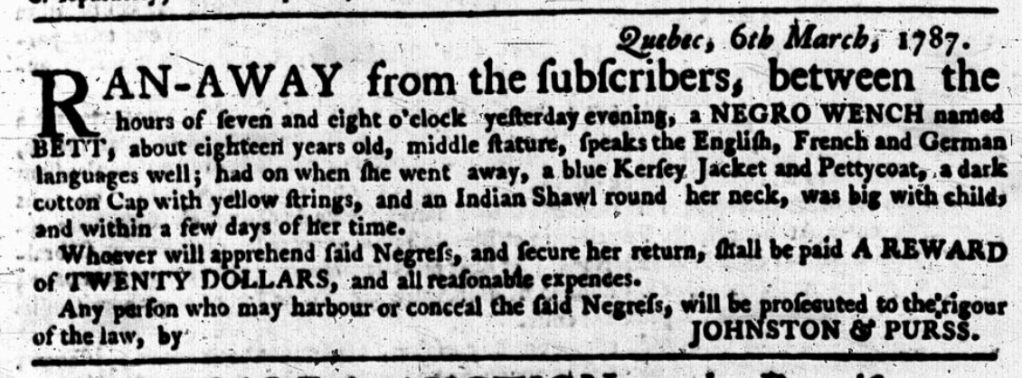

On The Quebec Gazette of 8th March 1787, an ad tells us about “Bett,” a woman about eighteen years old who, wearing a jacket, pettycoat and a shawl, had ran away the previous evening. The ad describes Bett as “big with child, and within a few days of her time:”

Though this ad’s goal was to help recapturing Bett and bring her back into the fold of slavery, in my imagination, I glimpse a young woman determined to claim freedom for her and her child.

This is one of the stories that I focus on in the chapter “Racialised Language in Colonial Newspaper Advertisements During the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries,” in the brand-new Routledge Handbook of Information History. This is the very first publication to come out of the project Racialized Motherhood, so I am writing this post to celebrate this milestone with you.

I looked into five case studies from newspapers across the English, French, Portuguese, Dutch, and Danish empires. Focusing on examples of published advertisements placed by enslavers to recapture freedom seekers, I took these short texts as my jumping off point to inquire into how language worked as a medium of racialization, and ultimately, of racism.

I didn’t want to simply denounce the demeaning language used to describe enslaved people in the Caribbean Islands, Brazil, and Quebec colonies that I deal with in this study. Beyond that, I paid attention to how language helped preserve, on the one hand, powerful traces of the people who resisted enslavement, and on the other hand, traces of the mechanisms that helped to congeal racism since in early moments of global capitalism.

The stories of Bett in Quebec, William in Saint Thomas, Catharine in Curaçao, José in Rio de Janeiro—not to forget that of the unnamed man in Basse Terre, Guadeloupe—are for me a reminder that racializing language did not just circulate within one colony, one empire, one linguistic group. Actually, it crossed borders and influenced how people of African descent came to be perceived around the world. By studying these short texts, my hope was to shed some light on how the racializing categories and hierarchies that continue to echo today have been constructed through our cultural practices, like reading the newspaper.

Leave a comment