By Danas Kuzminas.

As an intern, joining the research team for the Racialized Motherhood project, my main task is to examine two newspapers (the Barbados Mercury and The Barbadian) printed in Barbados during the 18th and 19th centuries. Even though the project aims to consider women with children or pregnant women who escaped their owners on the island of Barbados, I am collecting all the advertisements posted by enslavers looking for escaped individuals, as well as any other relevant findings such as lists of jailed fugitives. One of greatest benefits of participating in such research is the ongoing process of changing, transforming, reaffirming, or challenging pre-existing knowledge. Looking at the newspapers is valuable because these printed sources serve as avenues for understanding the society that existed at the time.

By slowly going through hundreds of issues by hand, it is fascinating to discover the representation of those found at the very bottom of the British Caribbean social hierarchy – the enslaved individuals subjected to colonial exploitation. As their status often barred them from written representation, their voices are difficult to uncover. As I began to observe the multiplicity of views expressed by the privileged parts of the British society, I came to grasp how the regime of slavery was an interplay between socioeconomic, political, and cultural (intellectual) forces. Each voice, positioned within their own social circle, had presuppositions, hopes, and beliefs that contributed to the construction of a supposed European moral superiority that maintained the colonial paternalistic vision. More broadly, British colonial exploitation and the establishment of an enslaved population tasked with generating wealth for the Crown and for private individuals rested on the widely accepted belief that such a system was acceptable and normal.

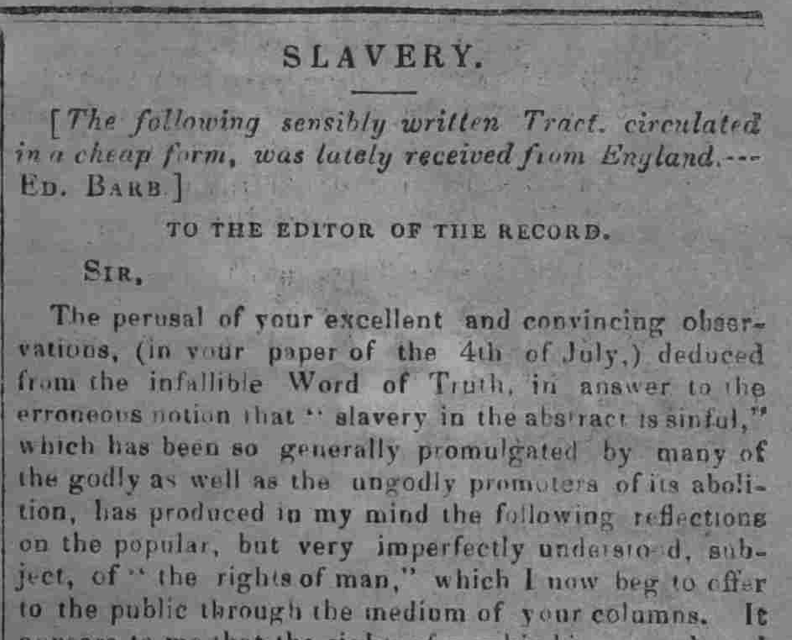

The Barbadian offers a fascinating view into the history of Barbados as it often printed opinion pieces that represented the current climate of affairs. One such piece was the religious tract printed on 1st January 1834, in which an unnamed author argued that slavery was not as sinful as abolitionists claimed (see Figure 1). Rather than grounding their argument solely in religious dogma, the author presented the existence of the slave/enslaver relationship as a natural dynamic. According to them, it entailed responsibilities and benefits for both parties; for the enslaver, the obligation to feed and clothe the enslaved person, while reaping the benefits of their labor; and, for the enslaved person, the obligation to work and the benefit of receiving protection. According to the author, the role of the enslaved person was to faithfully submit to their owner. The author supported their position by invoking the belief that every person on earth, while possessing a right to protect themself, must ultimately submit to a power above them – thus providing justification for slavery.

At the time, it was a widespread belief that human groups were fundamentally different from each other, with some deemed incapable of entering the civilized and accomplished European world. Some may have found reasoning in the Euro-centric philosophy of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, who argued that it was the Germanic (Western) world that embodied a modern and rational state with the highest level of consciousness. Additionally, there was the philosophy of Aristotle and his idea of natural slaves. According to him, some humans were simply superior based on their natural talents, and others were inferior, and should therefore be obedient. These distinctions positioned enslaved individuals as outsiders. Olwyn Mary Blouet goes on to support the idea that the enslaved experienced a ‘social death’, a term Orlando Petterson used to describe their exclusion from legal and political environments.[i] The commodified status of the enslaved produced through processes of depersonalization and desocialization made the stigmatizing narratives of enslaved people being incapable, vicious, and uncivilized credible to Europeans and colonists.[ii]

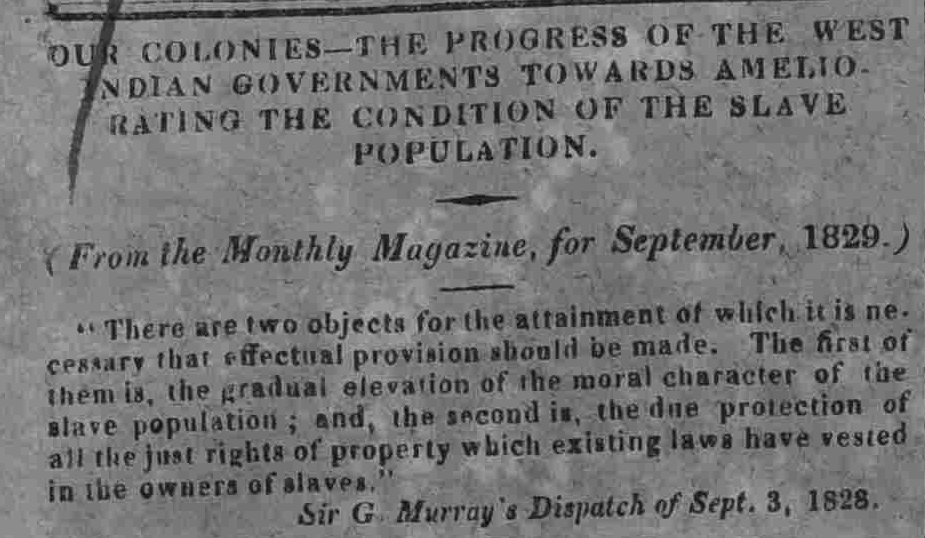

On the first day of 1830, a historical piece published in The Barbadian began with a quote from the prominent military officer and politician Sir George Murray (see Figure 2). At the time, he served as Secretary of State for War and the Colonies under the Duke of Wellington’s administration. He presented the metropolis’ intentions toward the enslaved population in the West Indies and their expectations for future change. In his statement dated 3rd September 1828, he had revealed two main objectives behind the proposed reforms of the slave system. First, he put forward that governments needed to cultivate a higher level of morality within the enslaved population, and second, that enslavers should be adequately compensated for the loss of their property. He went on to suggest that their primary motivation for the implementation of progressive improvements (amelioration) was so that enslaved people could ascend to the level of civil society and eventually obtain their privileges.

Olwyn Mary Blouet discusses how, following rising opposition to slavery, British pre–occupation with ameliorative policies to improve the general conditions of slavery through initiatives such as baptism, marriage, and church attendance, was closely related to religious civilizing processes.[iii] It becomes evident that such efforts were highly controlled, with skills such literacy, perceived as dangerous to the establishment by many. Blouet concludes that educational efforts prior to emancipation helped reduce the negative imagery associated with enslaved populations and facilitated their acceptance in certain parts of British society.[iv] Such a move promised hope for the soon-to-be freed individuals.

Following the abolition of slavery on 1st August 1834, the formerly enslaved were free only in theory. They were placed into an apprenticeship system, under which freed individuals were to work up to 45 hours unpaid per week, for their formers owners. Nigel Biggar argues that on smaller islands such as Barbados there was little possibility to attain their own land, meaning that employment under these poor conditions was the only way of surviving.[v] This system lasted until 1838, and the freed population faced financial, educational, and societal divisions and complications for generations to come.

Even as public awareness of moral objections to slavery took hold amongst British subjects, humanitarian sentiment remained intertwined with beliefs of European superiority that continued to entrench the existing and arising inequalities. Looking at the knowledge that was transmitted through print media can tell us how civilizing discourse continued to place freed people into realities where imperial discourses prevailed. However, the voices of the enslaved were not represented. Marisa J. Fuente writes about this in her book Dispossessed Lives: Enslaved Women, Violence, and the Archive. She argues that as the enslaved individuals were usually not a part of the discussions regarding abolition, it was primarily white men from the social groups of planters, merchants, parliamentarians, abolitionists who determined how emancipation unfolded.[vi] Therefore, as we look at these pieces of the colonial past, we must be aware that what we see may have been designed to fit into the imperial discourse. As we read sources “against the grain”, we are also able to identify the circumstances and reasonings that have facilitated and validated the slavery regime. Moreover, it can inform us about how slavery became normalized and about how the process of emancipation may also have functioned as a tool for setting the conditions of freedom in a moralizing discourse. I am interested to learn more about these power dynamics as I continue to examine the Barbadian newspapers over the next couple of months.

[i] Olwyn Mary Blouet, “Slavery and Freedom in the British West Indies, 1823-33: The Role of Education,” History of Education Quarterly 30, no. 4 (1990): 627.

[ii] Blouet, “Slavery and Freedom in the British West Indies, 1823-33,” 627-28. Quoted in Orlando Patterson, Slavery and Social Death: A Comparative Study (Cambridge, Mass., 1982), 1-101.

[iii] Ibid., 629.

[iv] Ibid., 642.

[v] Nigel Biggar, “Britain, Slavery, and Anti-Slavery,” History Reclaimed, August 16, 2021, 13.

[vi] Marisa J. Fuentes, “Jane: Fugitivity, Space, and Structures of Control in Bridgetown,” in Dispossessed Lives: Enslaved Women, Violence, and the Archive (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016), 13.

Leave a comment