By Danas Kuzminas

As I worked through hundreds of fugitive advertisements printed in Barbados during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the research process proved increasingly challenging. Although many of the ads I observed may initially appear uniform, closer examination reveals a wide variety of formats through which enslavers sought to inform the public about those who had escaped. Each advertisement constructs an image of an individual, a group, or an entire family, whose devastating histories and lived experiences are filtered through the dominant colonial narrative.

The Caribbean region was a vital asset for colonial empires, whose wealth was built upon plantation production sustained by the forced labor of enslaved people. On an island such as Barbados, where all land was occupied and controlled, there was little room to flee and even less space to remain unseen. For many, escape was an act of hope undertaken under conditions that offered few chances of survival. Today, as we attempt to write their histories, we are left with hundreds of fugitive advertisements—brief, fragmented records that reveal less about who these individuals were than about the violence of the system that sought to recapture them. Yet within these traces remain echoes of resistance, movement, and lives lived beyond the limits of the archive.

In this blog post, I have chosen two advertisements about Kitty Pender and Sukey Frances — women who were reported as fugitives at different moments within my period of analysis. Both women appeared in the Barbados Mercury, a newspaper printed on the island during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, known in the early nineteenth century as the Barbados Mercury and Bridgetown Gazette.

For me, located far away from the original archival materials, the availability of digitized material presents both opportunities and challenges. It requires careful attention to move beyond seeing the individuals merely as names, and instead to examine their representation as constructed through colonial, objectifying language. I resonate with Amalia S. Levi’s observations on how access to digitised archival material alters our sensory attention, where our brain prioritises input through vision.[i] Her point is particularly meaningful for someone like me, located far away in time and space from where the lives of these fugitives unfolded, as she suggests that any subsequent analysis may be shaped — and at times disrupted—by the scholar’s own background and positionality.[ii]

I have also drawn on Marisa J. Fuentes’s scholarship to understand the elements that owners chose to emphasise in their advertisements. In her book Dispossessed Lives, Fuentes notes that details such as “country marks” (scarification) can indicate the identities of enslaved people.[iii] Similarly, Levi highlights how fugitives may have been known by multiple names, whether given by an enslaver or parent, or acquired at baptism.[iv]

It is crucial to approach the representation of enslaved women with care, as they were rarely presented on their own terms in colonial sources. Here, I draw on Fuentes’s concept of “mutilated historicity,” which describes how enslaved women appear in the archives as physically and socially violated through descriptions of their appearance, past experiences, and the abuses they endured.[v] As Levi points out in her analysis of the Barbados Mercury, the promised rewards, mentions of family members, and information on whereabouts present in these advertisements sometimes reflect not only the urgency of recapture, but also the economic interests of the enslaver, such as potential income from the sale of the enslaved woman for sexual exploitation.[vi] In this blog post, I use the perspectives of scholars such as Fuentes and Levi to analyse two fugitive advertisements, examining several focus points enslavers have used in their ads and what those points tell us about these women and their lives as they became unwillingly portrayed inside of an objectified colonial discourse.

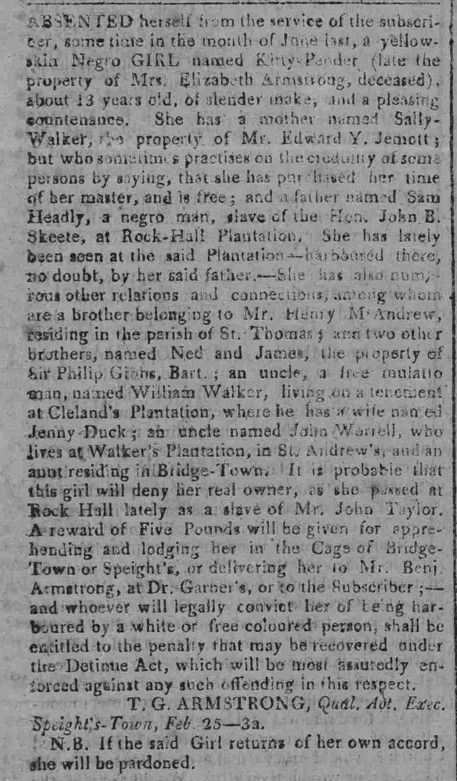

Figure 1. Kitty Pender’s ad, The Barbados Mercury, and Bridgetown Gazzette, 29 February 1812. Barbados Department of Archives. https://doi.org/10.23636/tykq-g425.

In the first example, from February 1812, we see that a girl named Kitty Pender (see Figure 1), had been missing since the previous June. Her importance to the enslaver is emphasized throughout the notice. She is described as having a pleasant countenance, a remark that indicates her aesthetic value to the enslaver and that objectifies her. She is thirteen, so she is around the age when free girls would begin to be considered marriageable.[vii] Her youth and attractiveness made her valuable for her reproductive labour. Crystal Nicole Eddins argues that women were relied upon to birth children who would expand enslavers’ property and sustain the plantation economy.[viii] The prices paid for enslaved girls and women were related to their reproductive capabilities, and certain laws have been continuously articulated to ensure that newborns would inherit enslaved status.[ix]

Kitty’s advert begins by naming her parents along with both of their respective enslavers. It specifies that she may be harboured at her father’s house, as well as listing the names of her brothers, uncles, one of their wives, and an aunt. It is clear that Kitty potentially had an extensive list of individuals with whom she might have found refuge. This suggests not only the breadth of familial networks in Barbados, but also how, even under an oppressive colonial system, knowledge of close contacts did not necessarily lead to the quick apprehension of a fugitive girl. Those who apprehend her are asked to either deliver her directly or bring her to “the Cage”. According to Fuentes, the Cage was a representation of colonial power in Barbados, where captured fugitives were confined until their enslavers claimed them, making it a tool of control.[x]

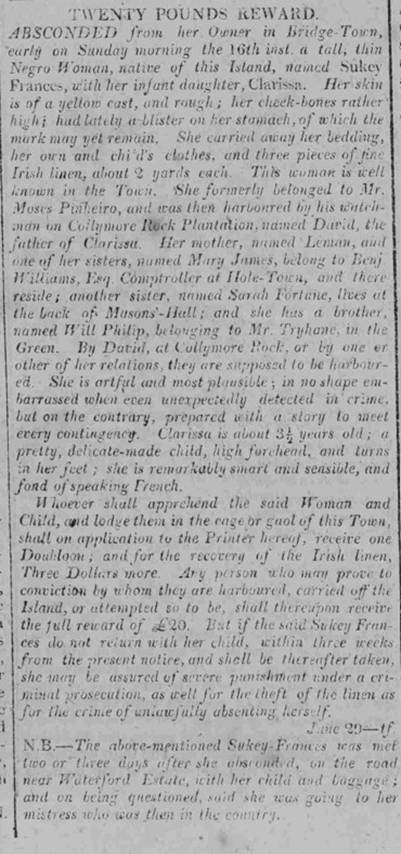

Figure 2.Sukey Frances’s ad, The Barbados Mercury, and Bridgetown Gazzette, 6 June 1811.Barbados Department of Archives. https://doi.org/10.23636/tykq-g425.

The second advertisement discusses a woman named Sukey Frances who had left her enslaver with her daughter, Clarissa. The enslaver begins by describing Sukey’s physical characteristics and mentions a blister on her stomach. It remains unclear whether this blister is connected to a skin disease or to physical abuse, as many enslaved women bore scars on their bodies that signalled the physical violence they had endured following their enslavement. The advertisement goes on to note that Sukey Frances was well prepared for her escape, having taken clothing for both herself and her daughter, as well as several pieces of valuable linen. The enslaver demonstrates awareness of multiple contacts who might shelter her, which once again points to the existence of a community that enslaved people relied upon. Clarissa’s father, David, is also mentioned; he is identified as a watchman and is noted to have previously been suspected of harbouring Sukey Frances. This suggests that this was not her first escape and that, given her many connections across the island, she was able to form and maintain relationships, including one with David.

The enslaver offers a three-week period in which she may return without punishment and specifies that she must bring Clarissa with her. This indicates that the mother and daughter, who had turned fugitives, were considered valuable property; they represented both current and future profit from their labour, including their reproductive labour. To ensure compliance, however, the advertisement concludes with an aggressive warning of criminal prosecution for her absence and for the linen she allegedly stole.

Both stories of these women are mediated through the enslaver’s perspective, a voice that seeks not only to punish and threaten the women themselves but also to intimidate those who risked assisting them. Through this lens, we come into contact with gendered violence. Sukey Frances’s status as the mother of a girl, and Kitty’s “pleasant countenance”, reveal how girls’ and women’s bodies were sites of control and exposure. As womanhood and motherhood were weaponized, the aim was not only to secure the fugitive’s return. The detailed descriptions of women’s bodies were intended to reduce them to commodities, their bodies legible for signs of ownership and assigned monetary value.

Working with digitised colonial newspapers from Barbados while sitting behind a laptop in the Netherlands has continuously challenged how I approach lives and cultures to which I do not belong. As someone privileged never to have experienced such forms of abuse, I can only try to engage with these archives with care and respect. Encountering fragments of more than a thousand individual lives in these fugitive advertisements from Barbados makes one reality unmistakably clear: some advertisements are painfully brief, stripping away all history and leaving nothing but a name for future generations, while others offer extensive descriptions. The language employed by enslavers varies as well, at times emphasising urgency, and at others promising pardons within a limited timeframe, revealing shifting strategies of control. Yet embedded within these notices is evidence of something more enduring: the existence of underground connections among the enslaved, their families, friends, and others willing to help. These networks were not incidental, but essential, enabling fugitives to plan escapes, remain in hiding, and, in some cases, to survive beyond the reach of their captors. In the Racialized Motherhood project, we see in particular the women and girls whose struggles for freedom were set against the objectifying gaze of the colonial regime.

[i] Amalia S. Levi, “’Runaway’ Ads as Records of Life Writing: Ariadne’s Story,” Life Writing, 22 no. 2 (2025): 339.

[ii] Levi, “’Runaway’ Ads as Records of Life Writing: Ariadne’s Story,” 339.

[iii] Marisa J. Fuentes, “Jane: Fugitivity, Space, and Structures of Control in Bridgetown,” in Dispossessed Lives: Enslaved Women, Violence, and the Archive (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016), 14.

[iv] Levi, “’Runaway’ Ads as Records of Life Writing: Ariadne’s Story,” 341.

[v] Fuentes, “Jane: Fugitivity, Space, and Structures of Control in Bridgetown,” 16.

[vi] Levi, “’Runaway’ Ads as Records of Life Writing: Ariadne’s Story,” 345.

[vii] Felicia Fricke, “Stability and Survival: Creole Widowhood in St. Eustatius, 1780s-1820s,” The History of the Family (September 2025): 11-12.

[viii] Crystal Nicole Eddins, “Racial Capitalism and Black Women’s Struggle for Reproductive Justice,” in Handbook of Gender Activism, eds. Jo Reger, Rachel L. Einwohner, and Kelsy Kretschmer (Edward Elgar, 2025), 335.

[ix] Eddins, “Racial Capitalism and Black Women’s Struggle for Reproductive Justice,” 334-335

[x] Fuentes, “Jane: Fugitivity, Space, and Structures of Control in Bridgetown,” 16.

Leave a comment