By Danas Kuzminas

Enslaved women on the island of Barbados were subordinated and subjected to harsh conditions shaped by the regime of slavery. Gendered discourses meant that enslaved women had to contend with multiple hardships at once. Among the most damaging were the stigmatizing and sexualizing discourses that we are researching in the Racialized Motherhood project. As we catch glimpses of the experiences of enslaved women through newspapers printed in colonial Barbados, these experiences are presented to us through the enslaver’s gaze. Historical processes and our world today continue to demonstrate how the truth was and is constructed by those who are in power. As we are presented with historical ‘facts’, rigorous awareness can help to unmask the biases they carry. This means that the same colonial paternalistic discourses that once stereotyped and racialized enslaved people can be used to inform us about their true agency within a slavery regime that controlled, abused, and exploited their existence for monetary gains.

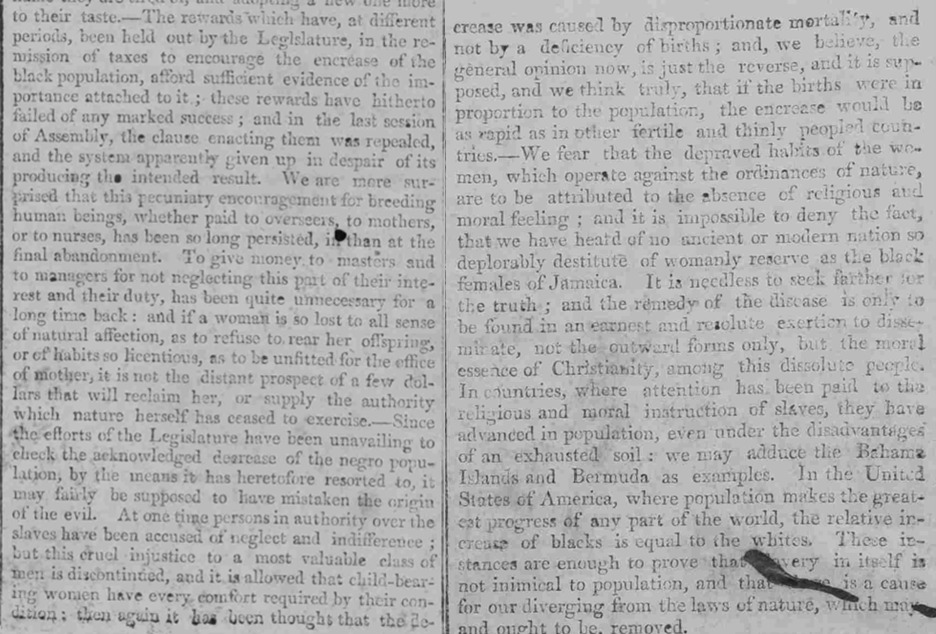

In August 1823, The Barbados Mercury and Bridgetown Gazette newspaper published an article discussing the dissemination of Christianity among the enslaved population, which had first circulated in the Jamaica Paper, showing the regional nature of the colonial regime. The article’s main goal was to argue that the decline in enslaved populations was the fault of women and their alleged immoral behavior. It begins by stating that religious instruction was necessary to improve moral character. The author(s) present arguments claiming that enslaved women had failed to fulfill what they called their duties in the ‘office’ of motherhood. Barbara Bush-Slimani argues that reproduction within enslaved societies was influenced not only by material factors such as diet or housing, but also by moralizing efforts that targeted cultural practices.[i] Efforts to ‘civilize’ enslaved women were inspired by ethnocentric myths that portrayed enslaved individuals as inherently prone to promiscuous behavior.[ii] Bush-Slimani calls our attention to the production of a stereotyped, homogenized version of African woman, in which her sexuality, pregnancy, and motherhood roles stripped away ethnic and regional diversity.[iii] According to her, the continuation of nurturing rituals and traditions, such as infant naming ceremonies or mothers allowing children to explore independently through nature as a means of discovering maturity, was viewed by colonizers as neglectful, and as lacking modesty, shame, and civilization.[iv]

To explore this issue further, I now turn to three women who escaped their enslavers with their infant children or while pregnant. The same fugitive advertisements that serve as proof of the commodified status of these women’s bodies also provide evidence that challenges the discourses in which these women were trapped. Exploring their multiplicity of strategies and forms of agency for reclaiming their motherhood is one of the most vital tasks of our project. Moving beyond the enslaver’s gaze can continuously contribute to a deeper understanding of the lived experiences of enslaved mothers.

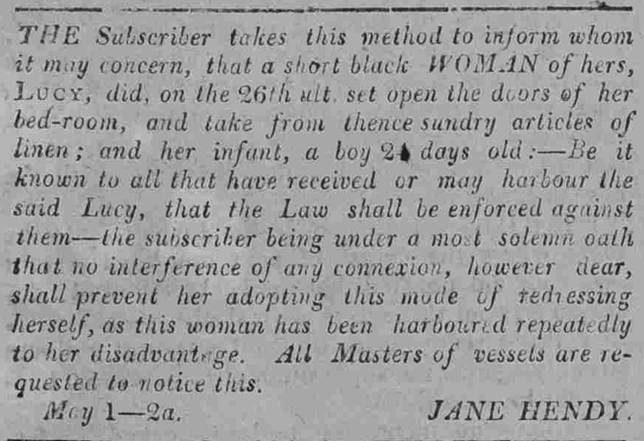

In the first advertisement, we catch a glimpse into the experience of Lucy, who has escaped from enslavement with her infant son, only 24 days old. Her enslaver also indicates that she had been concealed before and that Lucy had the ability to mask her true identity. Evidently, Lucy had been most likely preparing for her recent escape and was maintaining a social network that facilitated her previous and current escapes.

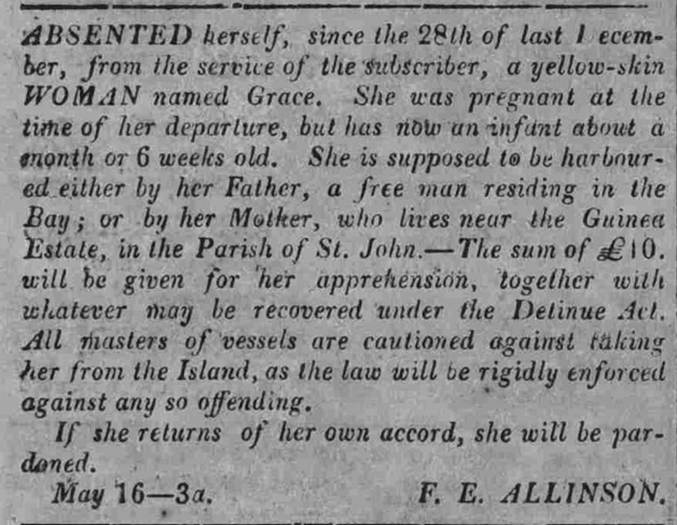

In the second advertisement, we are introduced to Grace, who chose to escape from her enslaver during her pregnancy. As she is now assumed to have given birth, her enslaver is motivated to locate and apprehend her. He or she is well aware of Grace’s closest contacts, such as her father and mother, who may be helping to conceal her. Similarly to Lucy’s runaway advertisement, Grace’s enslaver used formulaic language asking masters of vessels not to facilitate her escape in any way. Maritime routes of escape, or seeking shelter with captains were one of the many escape routes enslaved individuals have chosen to pursue. According to Jerome S. Handler, fugitives had the greatest chance of remaining concealed from their enslavers by entering urban situations or escaping using maritime routes.[v]

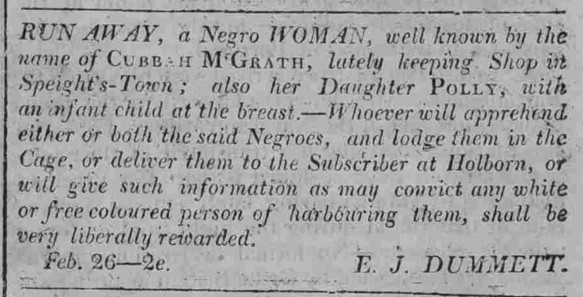

In the final example, we encounter a multi-generational escape from enslavement. It involves the woman Cubbah McGrath, who escaped her enslavement together with her daughter Polly, who had recently given birth to a child. This intergenerational flight ensured that these women took part of their support network with them when they fled.

The fugitive advertisements discussed above provide examples of how enslaved women sought to protect their children. Resilience and determination are key factors here, as they directly undermine the discourses that enslavers used to discredit and control these women. By dissecting colonial paternalistic frameworks and moving beyond the intentions of enslavers, we can see these women as capable of exercising the agency available to them, seeking assistance from social networks willing to support them. Escaping to other destinations required careful planning and resourcefulness.

The fugitive advertisements do not mention specific cultural practices, such as later weaning, that may have been prevalent among women from certain African societies, practices enslavers could have used to argue that women were incapable of caring for their children.[vi] Nor do they inform us about the harsh realities of endemic disease, dietary deficiencies, poor sanitation, or psychological and physical conditions that directly shaped these women’s experiences of motherhood. However, the advertisements do reveal that women who escaped with their infant children demonstrate clear intentions to seek shelter or to resist allowing their child to remain within the brutal realities of enslavement. This would also give them the opportunity for their own cultural practices of motherhood without interference from their enslavers.

Moving beyond the enslaver’s gaze and seeing what is absent or obscured in colonial printed media is an important priority of the Racialized Motherhood research team, allowing for a more nuanced understanding of motherhood under a system to which these women never consented. By examining the experiences of enslaved women and the risks they undertook, we can directly challenge the derogatory frameworks of colonial print media to portray them as caring, brave and resilient mothers acting under a system of oppression. Contrary to the 1823 article in the Barbados Mercury and Bridgetown Gazette, fugitive advertisements portray enslaved mothers as refuting colonial narratives at the very moments when they fought most strongly to protect and care for their children.

[i] Barbara Bush-Slimani, “Hard Labour: Women, Childbirth and Resistance in British Caribbean Slave Societies,” History Workshop, no. 36 (1993): 83.

[ii] Bush-Slimani, “Hard Labour,” 83.

[iii] Barbara Bush-Slimani, “African Caribbean Slave Mothers and Children: Traumas of Dislocation and Enslavement Across the Atlantic World,” Caribbean Quarterly 56 no. 1-2 (2010): 71.

[iv] Bush-Slimani, “African Caribbean Slave Mothers and Children,” 74.

[v] Jerome. S. Handler, “Escaping Slavery in a Caribbean Plantation Society: Marronage in Barbados, 1650-1830s,” NWIG: New West Indian Guide/Nieuwe West-Indische Gids, 71 no. 3-4 (1997): 184.

[vi] Bush-Slimani, “Hard Labour,” 84.

Leave a comment